We have been fairly successful at producing our own compost in Alaska and want to share our methods and techniques.

Composting is the process of breaking down organic materials into compost, typically for use in gardening applications.

Compost is great for enriching soil with natural nutrients that will help plants grow better. It is also helpful for simply “getting rid” of garden waste, turning a worthless refuse into something very valuable.

The Two Types Of Composting

There are two types of composting that are largely recognized. These are cold-composting processes and hot-composting processes.

Cold Composting Basics

Cold composting should be pretty familiar to most people. It’s fairly well known that organic matter will break down eventually and return to soil. Any time you see a rotten log on the ground, that’s effectively the cold composting process in action.

When we intentionally cold compost, we essentially pile up organic materials and allow this lengthy process to happen. Bacteria and microbes will invade the pile and slowly break down the organic materials into compost.

It can take months to years to get everything to fully break down, but eventually, you’ll be left with compost.

What’s great about cold composting is there are no rules or guidelines to follow. If it’s organic, it will break down into compost eventually.

Hot Composting Basics

Hot composting, however, is the process of optimizing the composting process to achieve the very rapid break down of various organic materials. With hot composting, there are a few more specifics you have to follow.

When an ideal ratio of “green” and “brown” materials are put together, it can create a perfect environment for the bacteria and microbes. When these thrive, the microbe and bacteria populations explode and you can get an extremely fast break down of materials.

Typically, with hot composting, you see a crazy increase in temperatures. Up to 160 degrees Fahrenheit is not uncommon! Thus, the term hot composting. Using hot composting methods, you can easily get finished compost in a matter of weeks to months.

What’s This About Green And Brown Materials?

When we talk about hot composting, the ratio of green and brown materials are important. So is understanding what these two materials are.

Effectively, green materials are high in nitrogen, whereas brown materials are high in carbon. These terms still don’t clarify the concept, though.

Fortunately, there are some general guidelines for these two material types in generally composted materials:

- Green Materials

- Food scraps

- Grass clippings/weeds

- Coffee grounds/tea leaves

- Manure

- Most garden waste

- Brown Materials

- Leaves

- Sawdust

- Wood chips

- Straw/hay

- Newspaper & cardboard

- Spruce/Pine needles & cones

- Wood ash

When we talk about the “ideal” ratio of green to brown materials for hot composting, there’s a little bit more to it than just how much of each material.

Ideally, you want about 3 to 4 parts of brown materials for every 1 part of green materials. Put another way, the hot compost pile should be about 75% brown materials and 25% green materials.

Remember, though, we’re talking about the basic components of nitrogen and carbon. Some brown materials have more carbon than others. Some green have more nitrogen then others.

What we’re really trying to do is get to roughly 75% carbon and 25% nitrogen in our material composition.

You can see that this can get seemingly complicated, quickly. We’ll get into this a little bit later, at least in the relationship of the materials that we use.

Also, it’s important to keep in mind that this isn’t a perfect science. Natural processes don’t need or follow exact amounts of anything.

Our Adventure Into Subarctic Composting

Some of our early research into composting indicated that cold composting was really the only viable option in the interior of Alaska.

We didn’t really know any better. Also, maybe this made some sense? But, in the end, we’re not the type of people that accept anyone’s advice as gospel.

As it turns out, that cold composting advice was completely wrong.

It’s very easy to get hot composting to work in subarctic latitudes, at least over the summer and shoulder seasons.

The best option that we’ve found thus far has been something like a hybrid approach of the two techniques.

We use hot composting over the summer and then leave our piles over the winter for a good cold composting.

Using these techniques, we have been able to get a very rapid production of compost. We aren’t waiting years for the process to break down the materials, either.

Getting A Compost Pile (Or Four) Going

A compost pile can be as simple as a pile of materials somewhere on your property. Let’s be clear about that, you only have to put labor into composting if that’s as far as you want to take it.

The size of a compost pile matters. Generally speaking, the larger the better. There are general minimum recommendations, which start at roughly a cubic yard of materials. Below that can work, but it increases the time it takes.

Some people build special containers for their compost piles, mostly for the purposes of neatly containing it. There are many options available, from dedicated bins to DIY solutions to tumbling composters.

Composting can take some time, so it’s also advantageous to have more than one compost pile going. This allows you to keep the primary stages of composting separate from one another.

The three primary stages of composting are the fresh materials when they are added to the compost pile, semi-composted materials and finished compost.

For us, we knew we had a fairly large amount of materials we’d be expecting to compost each year. We also wanted to produce a fairly large amount of compost, too.

So, that meant that for our purposes, we had to look at something both cost effective and provided for a decent size of composting capacity.

Finding The GeoBin Composting Solution

We assessed the various compost bin solutions out there. There are a number of methods and designs that you can use, all effectively with similar or identical results.

While DIY options were attractive to us, the lumber costs and construction time were a factor. Although pallets are theoretically free, getting pallets still takes a fair bit of labor in finding and acquiring them.

There are super low tech options, like making them with chicken wire or hardware cloth. I’ve worked with these before and there are a number of drawbacks that made them less palatable to us. We do like the mobility and flexibility of wire fence compost bins, though.

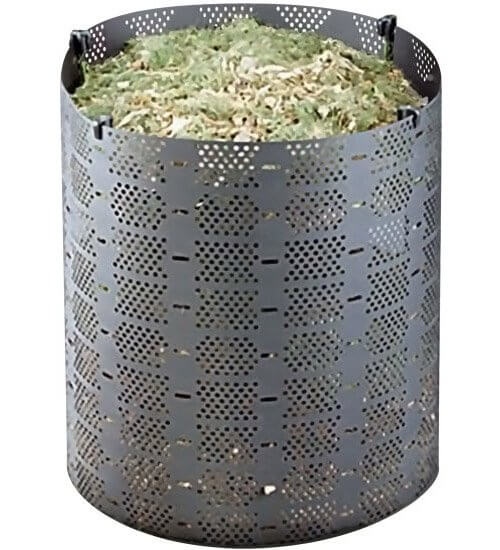

After quite a bit of research, we settled on the GeoBin solution.

Patrick over at OYR Frugal & Sustainable Organic Gardening really turned us onto them. Here’s Patrick’s video on his use of the GeoBin compost solution.

The thing we liked most was that the GeoBin solution was extremely scalable. If we undersized our system, or needed more capacity in the future, it was as simple as adding more units.

For $35, we could easily add another 216 gallons of compost storage space at any time. That was huge for us and the great news is they aren’t out of the ballpark expensive. (Definitely cheaper than wood!)

The GeoBin is both relatively inexpensive and also very efficient at composting. The design promotes high air circulation within the compost pile, which is a huge benefit in the composting process.

Working With GeoBin Composters

Setting up Geobin compost piles is really easy to do.

While you can use the GeoBin’s without posts, the addition of support posts really just makes things easier. Call it a composting comfort.

We opted to install four fence posts in the ground and wrapped the GeoBins around them. This provided excellent stability of the GeoBin, whether it was full or not.

Our posts are spaced about 30 inches apart from one another. You could probably use up to 32 or maybe even 36 inch spacing. We leave a 24 inch gap between the Geobins, enough to get a weed eater through.

This is an image of the four GeoBins that we installed. The four bins offer us a ton of flexibility, from storing raw materials as well as handling a decent volume of compost production.

This is an image of the four GeoBins that we installed. The four bins offer us a ton of flexibility, from storing raw materials as well as handling a decent volume of compost production.

We were really glad we went with the modular approach of the GeoBin compared to a more traditional DIY lumber based three bin solution.

We did an initial trial and then quickly expanded to the four units we have now once we had proved they worked in the subarctic. We even added two more for an inexpensive overwinter soil storage method.

We have also had to move our compost piles on our property, which further affirmed the Geobin’s ease of use.

Setting Your Subarctic Property Up For Long Term Composting Success

Most people that get into composting have an excess of green materials. From grass clippings to garden clippings, green materials are almost always in high supply.

If you recall the ratio for hot composting, you need a lot of brown materials to provide carbon for the process. We had to really think about where those brown materials were going to come from.

This is a very common problem for most people that get into hot composting. Plentiful supply of one, but not the other.

While we do have access to cardboard and infinite amounts of junk mail, this wasn’t quite the ideal solution for us. While we do have some deciduous Birch trees that provide some leaves, they weren’t in sufficient supply over the entire summer.

When we looked at our property, it was obvious we had access to a fair amount of wood. From our firewood processing to the management of trees on our property, wood was the obvious choice of brown materials for us.

With composting, however, it’s less than ideal to throw chunks of bark and entire branches into your pile.

Chunky materials will break down very slowly. You ideally need to get the wood into a manageable and usable form. Breaking down wood into wood chips makes for a much more rapid decomposition process.

How To Prepare Wood Sources For Composting

It became obvious, we were going to need a tool to get our plentiful supply of wood into an appropriate form for composting. The right tool for the job was a wood chipper, sometimes called a chipper/shredder.

While we could have rented a wood chipper each year, it made some sense for us to buy a good wood chipper. We were going into this composting process for the long term. We are also familiar with renting gear and there’s a number of drawbacks to renting equipment.

While owning equipment can be expensive, it also provides flexibility and does become less expensive than renting in the long term.

We decided to go with a mid-grade Echo Bear Cat chipper shredder. This unit is quite a bit above entry grade chippers and at the beginning levels of “professional” grade chipper products. Buy once, cry once is our motto.

As it turned out, the wood chipper also solved some other problems for us.

- We were accumulating a lot of birch bark from our firewood processing.

- There are also countless piles of branches across our property that we’d like to clean up at some point.

- We had several trees we needed to fell and knew we’d have a lot of excess branches to get rid of.

- We have about an acre of forested property, it would be nice to have a means of managing it without needing massive burn piles.

What it really came down to was that owning a chipper allowed us to turn a plentiful product on our property into a useable form. While burn piles are fun, they don’t result in anything particularly useable other than ash.

The wood chipper allowed us to practice a greater degree of permaculture on our property and also created the supply of brown materials we needed for composting.

The Subarctic Approach To Hot Composting With Woodchips

With a sufficient supply of green and brown materials solved, we sought to establish our hot composting strategy.

The best overall process we’ve found is to generally “stockpile” our brown materials.

We’ve spent a fair bit of time cleaning up the firewood bark and branches lying around our property. All of these were turned into wood chips with our chipper/shredder.

Conveniently, we store our wood chips in one of our GeoBins. This was a big reason for having four GeoBins, as opposed to three of them. This stockpile allows us ready access to brown materials the entire season, while the green materials come in.

While most compost guides generally talk about “layering” green and brown materials, we generally just mix the wood chips in with our green materials. We put several buckets of wood chips for each load of green materials. We also generally try to mix them together, ensuring great green/brown contact.

It’s probably important to further clarify the green/brown ratio concepts we mentioned above. The specified ratios are not specifically the amount of the materials, but rather the ratios of nitrogen to carbon.

Wood chips are an extremely potent source of carbon. They are far and above greater in carbon compared to other sources such as leaves or cardboard. Thus, in our piles, we’re not actually mixing in 75% of the wood chips – it’s typically far less than that.

If we had to guess, to get successful hot composting with wood chips, we’re generally adding roughly 5-10 gallons of wood chips per 30-50 gallons of green materials.

Put another way, that’s about 1 part of brown materials (wood chips) to 5 parts of green materials (almost everything else we compost).

To figure all this out, we really just eyeballed the mixture, based on how it performs and looked. We use these general guidelines to make sure we’re on track:

- If we have temperatures above 140F in a few days, our mixture is good enough for our purposes.

- Should the pile appears too moist/wet/sloppy, we generally take that to mean we need more carbon (or wood chips).

- If the pile appears dried out, we add water. This can often also indicate you need more nitrogen, or green materials.

- If the pile is mostly wood chips, it needs more green materials.

We don’t honestly know the exact ratios of carbon to nitrogen, we’re just basing accuracy based on how the pile performs.

We can surmise that since we’re often able to exceed 160F temperatures in our compost pile, that we’re definitely around that 75% carbon to 25% nitrogen ratio.

The Hot-Cold Hybrid Approach To Subarctic Composting

We continue the GeoBin mixing process throughout the summer season. It’s important to take advantage of the weather while you have it.

They say you should add all your material at once, but that’s not how we do it. We just add as things come in. Again, because we stockpile our brown materials, we can easily mix in carbon to any nitrogen we add to the pile.

Once the bin is full, we leave it alone until it significantly reduces in size. (Typically, about a month or whenever we get around to it.)

Once the pile is significantly reduced, we turn the pile into another GeoBin. This re-invigorates the composting process. If possible, we try to combine multiple bins of around the same material together, again trying to create a full GeoBin.

We try to turn our piles once or twice a summer. This doesn’t include the harvesting, which also results in another turn of the materials twice a year.

Eventually, though, the six month winter will settle in and we shift from hot composting to cold composting.

The fully mixed GeoBins proceed to sit for the entire winter. We don’t do anything to the piles over the winter – neither turning them, nor adding to them.

Harvesting Your Subarctic Compost With A Cadence

We harvest our subarctic made compost twice a year.

We harvest in the spring, once the pile has fully thawed (typically late May) and also once again before winter.

To harvest our compost, we use a home built compost sifter to separate the compost from the materials that still haven’t broken down.

This sifter is just some 2×4’s formed into a rectangle with 1/4 inch galvanized steel hardware cloth that is screwed (with washers) and stapled to the bottom.

We built our sifter to fit over our wheelbarrow. This allows us to easy sift our compost right into a wheelbarrow for further transport.

This is our DIY compost sifter. It’s literally 2×4’s with hardware cloth attached to it. Pretty simple and relatively inexpensive. We built ours to fit our wheelbarrow.

We scoop our mix of materials into the sifter with a pitchfork and shake out the compost into our wheel barrow.

Material that doesn’t fit through the hardware cloth is returned to a new material GeoBin for further composting. In the fall, we usually try to mix in our garden and yard cleanup materials in with this material as well.

This is pretty typical of the material that we get that can’t fit through the sifter’s hardware cloth. Adding this back into nitrogen rich compost piles will quickly accelerate the composting process. The majority of this material is unfinished wood chips.

We’ve found it worthwhile to again sift the material in the spring, prior to restarting the hot composting process. The winter-long cold composting process is quite efficient as there are high numbers of bacteria and microbes all ready in the pile.

The reality of subarctic composting is that your compost pile is a solid block of dirt ice. At least until it fully thaws. Obviously the timing of the above progression of sifting and restarting the hot-composting process depends entire on the state of the pile. That’s the Alaska life.

So, basically, this means we are harvesting our compost twice a year. Once in the spring, and once right before winter. Although we could probably be more aggressive, harvesting is a big job and it’s nice to only do it twice a year.

Occasionally, the moose stop in at the pile for a winter snack. That’s just how it goes here in the north.

Producing Large Amounts Of Subarctic Compost

In most years, we are able to produce around 150 (or more) gallons of finished compost using the above methods. This was quite a bit more than we originally expected.

This was with three to four active GeoBins, which represents almost 900 gallons of composting capacity. We don’t use them nearly to full capacity currently, but the four GeoBins are about the right size for our composting needs.

This was with three to four active GeoBins, which represents almost 900 gallons of composting capacity. We don’t use them nearly to full capacity currently, but the four GeoBins are about the right size for our composting needs.

Once the compost system gets going, it really only requires occasional turning and bi-annual harvests. After having done it for several years, you fall into a bit of a cadence for the schedule.

As for the quality of the compost, it’s quite decent. We are not surprised by the heavy “woody” content of the compost, that’s to be expected when you use wood chips as your source of carbon. It’s not excessively woody, though, and features a rich appearance. It’s similar to most bags of compost you would actually buy.

The one drawback to subarctic composting is it’s not something you want to be dealing with in the winter. Thus, it really only works for us over the shoulder season and summer months, currently.

We might add a trash can near the house that would easily allow us to store compost scraps over the winter. We would add these to our piles come the beginning of spring, after our first sift.

Other Uses For Geobins Around The Homestead

As we had a fair bit of experience with the GeoBins from a composting perspective, we began to think of them as a possible tool.

We now use a couple of additional GeoBins for storing our container garden soil over the winter. This has been quite an ideal solution for us, as we operate a considerable size container garden.

Geobins offer a convenient method for storing that soil. Additionally, we’re getting a little bit better composting of the roots than we did previously. This means the soil is even better off for re-use the following season.

That’s All We Wrote!

Having a good time? We have an ever growing list of insightful and helpful subarctic & cold climate gardening articles, waiting out there for you!

- Cold Climate Gardening Basics 👉

- Growing Your Garden From Seed Indoors 👉

- Advanced Cold Climate Gardening Techniques 👉

- Plant Specific Cold Climate Growing Guides 👉

- Subarctic Perennial Food Forests & Foraging 👉

- Indoor Garden Lighting & Grow Rooms 👉

- Greenhouses & Temperature Control 👉

- Harvesting & Food Preservation 👉

- Solving Cold Climate Garden Problems 👉

- 1 Minute Reads On Tons Of Garden Topics 👉

FrostyGarden.com is 100% ad-free and we do not use affiliate links! This resource is voluntarily supported by our readers. (Like YOU!) If we provided you value, would you consider supporting us?

Good article Jeff. I think I may purchase one or two of the geo bins for myself in Montana.

Thanks for the post. I would like to use willow/alder chips. What type/size chipper would you recommend?

You are welcome! I would suggest avoiding the very inexpensive (~$100) “Sun Joe” type chippers as they are under powered and somewhat flimsy. Beyond that, chippers are rated and priced typically by the engine size as well as the branch size they can handle. 2 or 3 inch varieties will fit most homeowner applications, we went with 3 inch as we have branches that large. It’s also nice to have the 2-in-1 chipper/shredder function for general yard debris. You can also rent chippers from your local equipment rental or home improvement store. Good luck and may you be swimming in compost!