If you are a grower, one of the best investments you can make in gardening is planting perennial fruits and vegetables.

When you live in the subarctic, such as in zone 2 or zone 3, you simply don’t have as much in common with our our fellow gardeners at lower latitudes.

Especially when it comes to growing perennials.

While there are many garden blogs and sites out there featuring perennials for warmer zones, there are very few that specialize on subarctic USDA zones.

It may come as a surprise to some, but there are a great many food bearing perennials that you can grow in the subarctic!

Almost a literal smorgasbord of choices!

What Is A Perennial Food Forest?

The term food forest is concept based in the practice of permaculture. It basically involves planting a perennial, low maintenance and sustainable plant based food garden.

At an advanced level, it involves a number of concepts that you can read about here. At a basic level, though, building a food forest involves intentionally planting food bearing perennials.

The food forest is usually separate from your normal garden. A food forest may also feature some annual plants that complement the perennials.

The food forest is usually separate from your normal garden. A food forest may also feature some annual plants that complement the perennials.

A food forest also doesn’t have to be a single, dedicated space. It could simply be a number of edible plants growing across your yard. It doesn’t even really have to involve anything that looks like a forest, either.

Perennial gardening is typically a much longer term gardening technique. The plants may not produce for several years. But, once it gets going, you’ll have very easy access to food, with very little effort, over the entire growing season.

The USDA Zone System & Perennial Plants

You’ve probably heard about the concept of “zones” or “hardiness zones” when it comes to gardening.

This entire concept is especially important when we start talking about perennial plants. Particularly so when we talk about subarctic perennials.

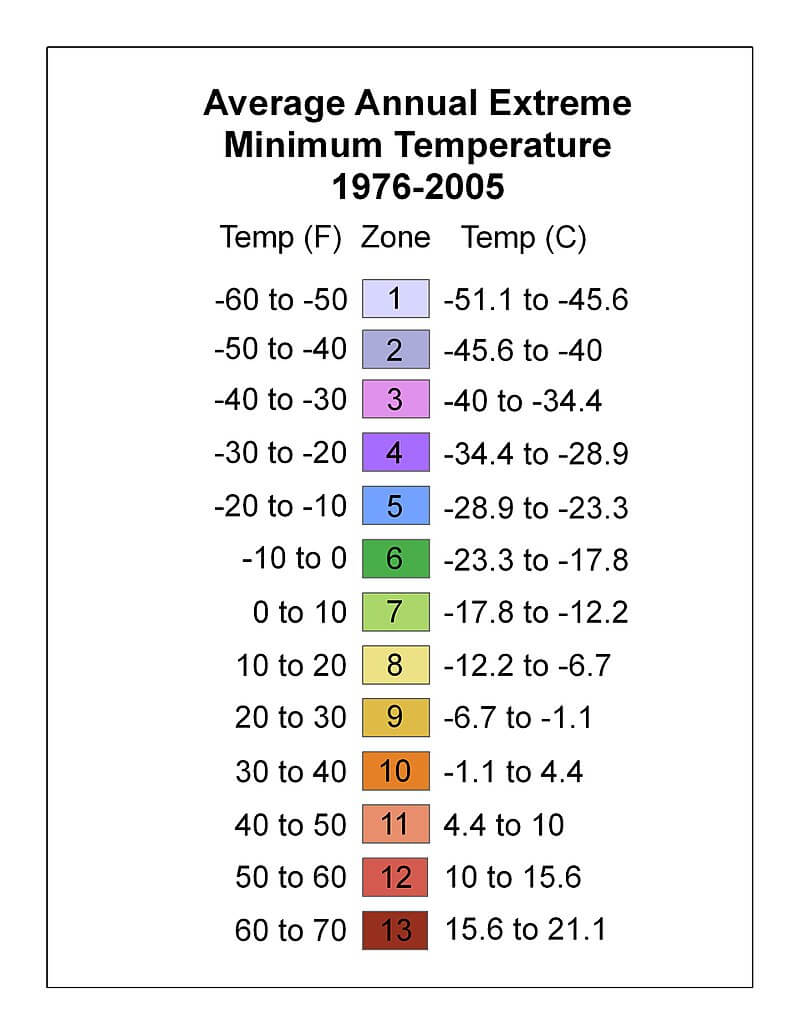

In the United States, these zones are essentially the dividing of various climates into thirteen unique classifications based on the most extreme minimum winter low temperatures.

Each zone also features a “subzone” (A or B) that defines the upper and lower temperature range of each zone. These zones are then applied to geographic regions based on where those extreme minimum temperatures are expected to be experienced.

These are the 13 major hardiness zones for the United States, and the expected low temperatures for those regions.

Perennial plants have a minimum temperature at which they will no longer survive the winter. Thus, all perennial plants will also have a USDA zone rating, indicating the regions where it could be expected to survive the winter in that area.

For our international friends, other countries also have similar zone systems!

For example, there is the “Canadian Plant Hardiness Zone system” and also the “European Hardiness Zone system.” While there is no official international zone standardization, most of the systems do try to share similar numbering and temperature range ranges to avoid confusion.

Demystifying Your Personal USDA Zone

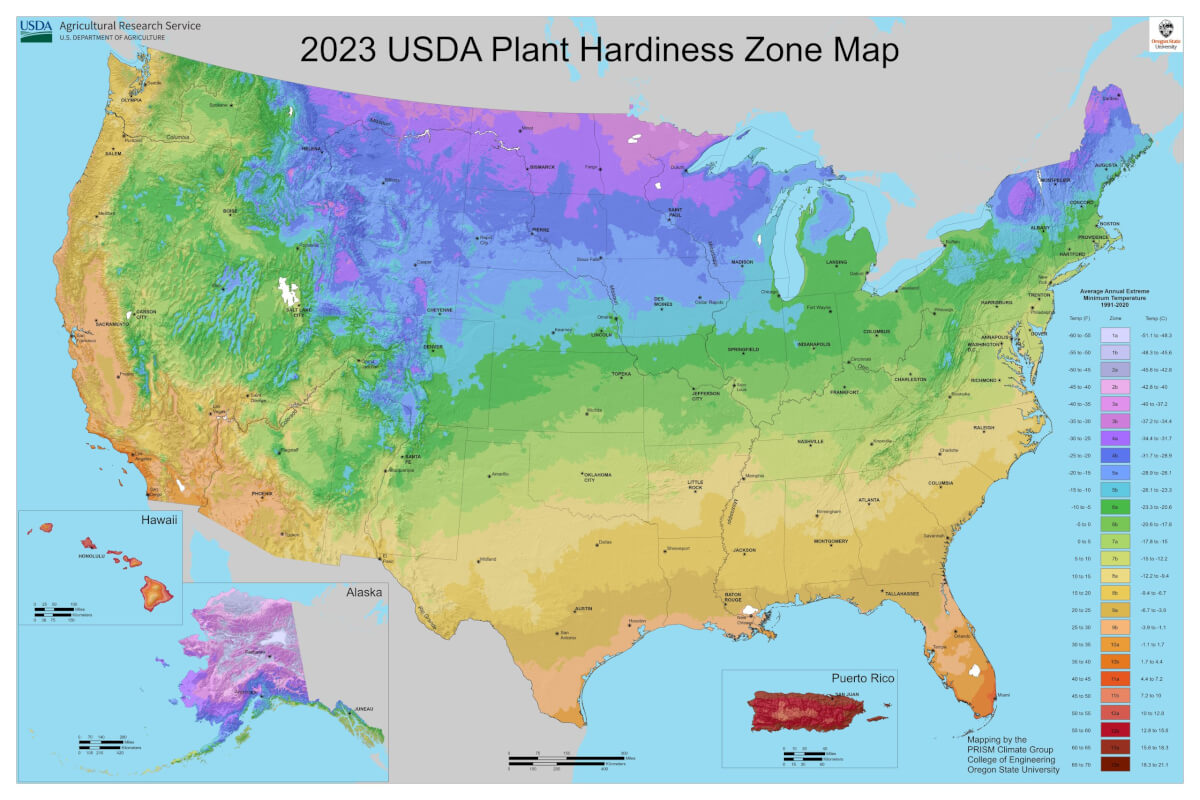

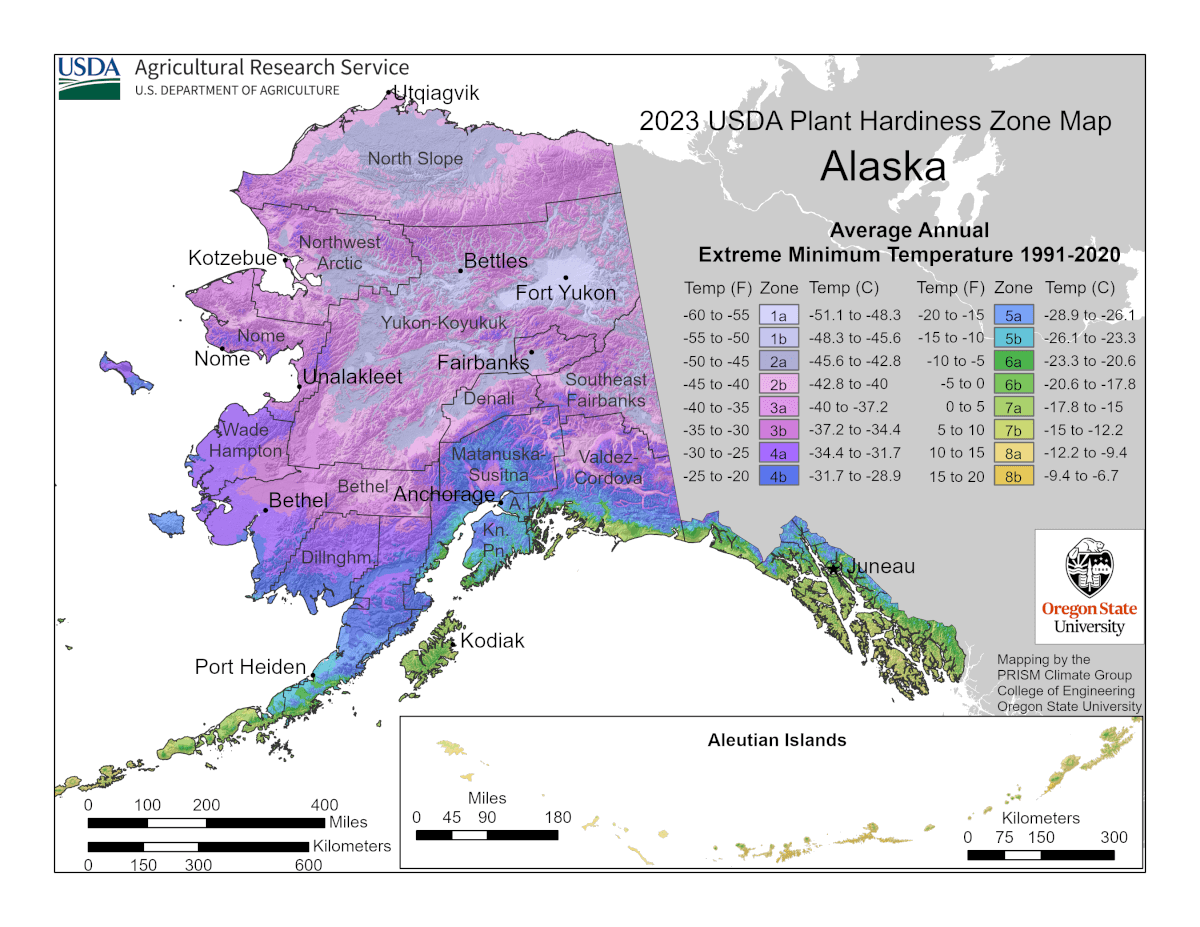

Most of the Interior of Alaska is considered somewhere between zone 1 and zone 3.

Whereas, much of South Central Alaska can reach zones 4 or 5. The southern tips of Alaska, including the Aleutians and southeast, can get all the way up to zones 6 through 8!

That’s eight different zones in a single US state!

Here’s the thing, though. These zones are general, but also specific. While there are guidelines as to what can be expected in your area, the exact zone you are in depends on exactly where you are at.

In 2023, the USDA released an updated zone map for Alaska with greatly improved data. They also have a street level map, which makes it much easier to identify your “theoretical” zone.

For example, our community garden is roughly a zone 1b. The city of Fairbanks is generally recognized as zone 2a. Our home is closer to zone 3a! These three places are at most 15 miles apart, so just looking at the USDA zone map is not always accurate!

The exact zone your specific yard is in will vary based on your elevation, general exposure and even variable voodoo like micro-climates. Learning your exact zone can take some experimentation with plants to actually determine!

Furthermore, say you live “on the line” of a major growing zone boundary. Say, for example, your neighboring town is zone 5a, but your location is zone 4b. Is there really a major difference in your climates? Absolutely not!

USDA growing zones are an imperfect system, but they give the gardener general advice of what to expect and what can be done.

Additionally, while plants are rated for specific zones, particular plants may be slightly more or even less hardy than they are rated.

It can also be that a given plant may do well in a certain area of your yard, but might not survive in another place. Sometimes, environmental factors like annual snow load can also help protect plants from the bitter cold, adding a whole zone for the plant.

With perennials, there are a lot of complexities that involve genetics and many different factors. It is very much open to experimentation and less defined by absolutes.

What Are Some Subarctic Perennials For Zone 2 and 3?

There is a fair bit of information out there on cold hardy perennial plants that do well in the subarctic climate.

It can be difficult, however, to find a comprehensive list of these plants. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt at a comprehensive list of perennial food bearing plants that can do well in subarctic climates.

Here we detail almost every commonly available perennial fruit or vegetable that we are aware of that might be compatible with subarctic environments. We’ve also included some wild cultivars that are sometimes commercially available.

These all come in at USDA zone 3 or lower, or hardy for the subarctic. Our friends in south central and southeastern Alaska have a lot more options out there, but it’s a lot more difficult to find perennial lists based on USDA zones 2 and 3.

Common Food Bearing Subarctic Perennials

There are a number of fairly common food bearing garden perennials that will do well, even in the interior of Alaska. Some of these include:

| Plant | USDA Zone | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Asparagus | Zone 3 | |

| Bee Balm | Zone 3 | |

| Chives | Zone 2 | Will spread by self-seeding. |

| Green Onion | Zone 3 | Try cultivar Allium fistulosum (aka Siberian onion) for best results. |

| Horseradish | Zone 3 | Spicy! Can get somewhat invasive, so plan accordingly. |

| Lovage | Zone 3 | Herb, tastes somewhat like celery. |

| Mint | Zone 3 | Highly variety and even plant specific, as most mint are zone 4 perennials. We suggest planting near sources of thermal mass, such as homes, for best success. |

| Raspberries | Zone 2 | Boyne is known to do well, but successful varieties can be golden and red varieties. |

| Rhubarb | Zone 2 | Widely reported as zone 3, but many zone 2 gardeners have success! |

| Strawberries | Zone 2 | Several varieties. Toklat is the strongest subarctic cultivar we've found |

Less Common Food Bearing Subarctic Perennials

Beyond the common garden perennials, there are a number of more obscure food bearing perennials that will also do very well in the Interior of Alaska. Examples of these include:

| Plant | USDA Zone | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| American Cranberry | Zone 2 | Also known as viburnum trilobum or high brush cranberry. |

| Arctic Raspberries | Zone 2 | Also known as Rubus Arcticus. |

| Aronia Berry | Zone 3 | Also known as Chokecherry |

| Asiatic Plums | Zone 2 | Also known as Prunus Salicina |

| Bearberry | Zone 2 | |

| Birch | Zone 2 | Sap can be turned into syrup. Catkins are also edible. |

| Cloudberries | Zone 2 | Also known as Rubus Chamaemorus. Usually wild, rare cultivars available. |

| Crowberry | Zone 2 | Also known as Empetrum Nigrum. Usually wild, rare cultivars available. |

| Currants (Golden, others) | Zone 3 | |

| Echinacea | Zone 3 | Also known as Purple Coneflower |

| Elderberry | Zone 3 | |

| Fiddlehead Ferns | Zone 3 | Harvested when very young. Commonly described as asparagus like. |

| Goji Berry | Zone 3 | |

| Gooseberry | Zone 3 | |

| Honeyberries | Zone 2 | Also known as Haskaps |

| Lingonberry | Zone 2 | Also known as low brush cranberry. Wild, some cultivars available. |

| Manchurian Crabapples | Zone 2 | |

| Manchurian Apricots | Zone 3 | |

| Nanking Cherries | Zone 2 | |

| Rhodiola | Zone 1 | Sometimes called "arctic root." Herbal. |

| Russet Buffaloberry | Zone 2 | |

| Saskatoon Serviceberries | Zone 2 | |

| Seaberry | Zone 2 | Also known as Hippophae or Sea Buckthorns. |

| Siberian Pear | Zone 2 | |

| Sorrel | Zone 3 | |

| Sunchokes | Zone 3 | Also known as Jerusalem Artichoke. Be careful, invasive species. |

| Walking Onion | Zone 3 | Also known as Egyptian Onion. |

| Wintergreen | Zone 3 |

Some good food forest plants aren’t necessarily perennial in the subarctic, but they are good at re-seeding themselves. Each year, they will drop next year’s seeds and you have a very good chance of it growing back in the same location. Examples of these are:

- Strawberry Spinach

- Cat Mint (aka Catnip)

- Chamomile

- Many plants that can successfully seed & disburse in ~3 months

A Word About Wild Cultivars

As you might have gathered, we included some plants in our list that are usually found in the wild. Alaska and the subarctic has a surprising number of food bearing native plants, typically berries, that grow in the wild.

These can be harvested from the wild, of course, but you have to know where to find them.

However, with the above listed species, there are sometimes cultivated varieties available.

This simply means that people are growing these particular varieties, by seed or other form of replication such as cuttings or rhizome division.

These wild, but cultivated, varieties are usually somewhat difficult to find. Nonetheless, they can be found. Often, due to their rarity, the price is often quite high as well. It is also possible to cultivate them yourself, but that’s well beyond the scope of this post.

If you think about it, almost all the fruits and vegetables available out there, most started with some sort of wild variety of that plant. Most of these have been cultivated for so long that we have been able to breed them with specific, beneficial characteristics.

This happens less so with subarctic varieties, simply because there is less overall demand for them.

We would suggest starting with some of the more common varieties that are out there. If you become particularly advanced in your perennial game, however, there are plenty of plants you can grow into.

Setting Your Subarctic Perennial Food Forest Up For Success

You could just willy nilly go out and plant these perennials in your yard. For best results, however, there are a few good practices you should use.

Mulching your plants is almost always a good idea. This will help reduce competition from any nearby native plants.

We like to use about 4-6 inches of wood chip around the plants. If your yard is particularly heavy with native plants, a layer or two of weed fabric or cardboard underneath the wood chips is also a good idea. This mulch layer will also help keep the root system warmer over the winter, allowing your plants a better chance at survival.

This picture shows our general approach to protecting our perennials from native grasses and weeds in a high-competition environment. This helps the perennial get a leg up, since there’s less surrounding competition.

It’s also not a bad idea to get some good quality soil in the ground for your perennials. This might be some home grown soil, some potting soil or perhaps just some compost. This will help the plant transplant well and provides a better soil for the plant’s roots to grow into.

For trees in particular, they are susceptible to moose eating their tops in the early winter. At least until your trees are substantial in size, it’s not a bad idea to surround them in either hardware cloth, chicken wire or a tomato cage.

Caring For Your Subarctic Perennial Food Forest

The whole point of the food forest is basically a perpetual garden on autopilot.

For the most part, you don’t have to worry too much about your perennials. They are hardy for the winter conditions and many are often accustomed to growing in less than ideal soils.

When you are planting perennials, it’s worth a little bit of effort in researching the variety that you are trying to grow.

When you are planting perennials, it’s worth a little bit of effort in researching the variety that you are trying to grow.

What type of soil does it like? Is it drought tolerant? Does it prefer shaded or sunny areas? Does it like to be companion planted with other perennials, like it might find in nature?

You do want to try and offer the plant the environment that it likes, as much as possible.

That said, you can improve results by using products like slow release fertilizers, or even adding them to your regular fertilization routines you might use on other plants. This will certainly give them access to more resources, which will ultimately help them grow faster and in better health.

As for regular watering, that’s up to you. It’s always a good idea to water for the first month or so after transplanting, at least until the plant is able to establish its roots.

When we experience drought conditions or extremely warm temperatures, we do try and water our perennials at least once a week. We want them to survive!

Strategically Starting A Subarctic Perennial Food Forest

The thing about perennials is that they are often expensive. It wouldn’t be a good idea to buy a bunch of them, plant them out and ultimately have them not survive.

When we started our subarctic food forest, we purchased a number of different perennials the first year. We wanted to see what worked and what didn’t work in our specific yard.

We knew our zone fairly well, but there are a number of factors that can influence plant survival.

Once we established what worked, we then have focused on adding a more sizable quantity of those varieties to our food forest. We try to focus on just one or two varieties each year so we can build up a meaningful supply of that variety.

This usually means we are now planting a six to twelve plants of a specific variety that we know does well in our yard.

Our ultimate goal is to have a meaningful supply of all sorts of subarctic perennials that will produce every year for us.

We continue to experiment with new varieties each year, again only planting one or two of each for the first year.

We usually set a budget each year for both the expansion of successful varieties as well as a few new introductions.

A Perennial Flower Game Is Also On Point

The subject of this post is certainly food focused. But, we do know that gardens benefit from the presence of natural pollinators.

Flowers are the number one attractor of pollinators.

We really only want to mention that we’re also playing this perennial game with various flowers as well.

While the purpose of flowering perennials is to diversify the life around our property, flowers can also help the northern gardener build a “pollinator magnet” for local bees and flies.

Providing an attractive pollination focused environment helps both the perennial food-game as well as the annual food-game. Those pollinators will “remember” your location for the smorgasbord of pollen you provide. You will be “on their map” if you will.

Failure Is Always An Option

If we’ve learned one thing from our subarctic food forest experimentation, it’s that accepting failure is part of the experience.

Growing perennials in the subarctic is not a straight forward process, as it might be in other southern latitudes. Our harsh environment and even differences from year to year present many challenges.

If your plants don’t make it, you’re not failing at gardening. You’re trying to do something more difficult and the risk of failure is much, much higher.

Some springs, we go out to our food forest only to find that a moose has decimated our plants over the winter. It sucks.

Just know, going in, that you’re not going to win every battle. You are going to win some and you’re going to lose some.

Notes On Apple Grafting In The Subarctic

One thing that we’ve found interesting is that there has been quite a few successful experiments related to apple tree grafting.

While the depth of this subject is outside the scope of this post, we mention it because it is directly related to the subject.

Grafting is the process of “joining” two entirely different plant varieties together. The plant’s natural healing processes “bond” the two different varieties together into a singular plant.

Apple trees are particularly well suited to the grafting technique.

The common subarctic application is to have a base plant (roots, main trunk, etc.) be a fully subarctic hardy variety. Grafted onto this hardy tree is a less hardy variety, which then grows to fruition and produces that particular kind of fruit.

This technique allows the subarctic gardener to grow apple trees that are well outside the zone they are being grown in.

We will conclude this by saying that this is not a simple subject. It requires much greater depth of research to determine successful varieties that can be grafted as well as the techniques that are used.

Go Forth And Grow Your Subarctic Perennial Food Forest!

We hope that our research and experience with subarctic perennials has helped you.

We definitely found some difficulty in locating a comprehensive list of zone 2 and 3 perennials that are great for growing in the subarctic. Such a thing needed to exist and now it does.

Did we miss anything that needs to be here? We probably did! Have anything else to add? Be sure to slap a comment below!

That’s All We Wrote!

Having a good time? We have an ever growing list of insightful and helpful subarctic & cold climate gardening articles, waiting out there for you!

- Cold Climate Gardening Basics 👉

- Growing Your Garden From Seed Indoors 👉

- Advanced Cold Climate Gardening Techniques 👉

- Plant Specific Cold Climate Growing Guides 👉

- Subarctic Perennial Food Forests & Foraging 👉

- Indoor Garden Lighting & Grow Rooms 👉

- Greenhouses & Temperature Control 👉

- Harvesting & Food Preservation 👉

- Solving Cold Climate Garden Problems 👉

- 1 Minute Reads On Tons Of Garden Topics 👉

FrostyGarden.com is 100% ad-free and we do not use affiliate links! This resource is voluntarily supported by our readers. (Like YOU!) If we provided you value, would you consider supporting us?

Hi from zone 1/2 Tok Alaska. On your fruits list you can add Seaberrys! They have been growing and fruiting for over 14 years now. Wonderful substitute for oranges and higher in vitamin C!

Good catch! We did miss that one, I’ll get it added right away here. Good looking out, thanks!

Hey there, I have a list of plants for zones 2 and 3 here, and have added your plants as well if I didn’t have them on there. Thanks!

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1l0qkyu8s9ATp9wXAns9v5ZfL7THzs5MlnFLV6VMPdfg/edit#gid=155337842

This list is great, Trent! Appreciate the deep research, definitely covers everything we have here and then some. There are a few on the list that I know aren’t zone 3, but I do think in general, more research really needs to be applied. As we mentioned in this article, sometimes microclimates and other factors can influence survival. There just aren’t absolutes when it comes to our climate. Thanks again, truly great information and perfect for this article!